What’s a microbiome?

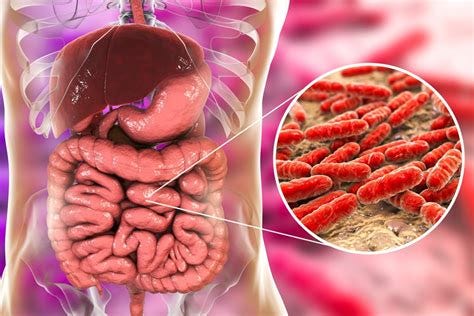

Let’s look at the word ‘microbiome’ for a second. It is split into 2 parts: ‘micro’ and ‘biome’. ‘Micro’ meaning small, and ‘biome’ meaning a very specific ecological community, characterised by certain living species and climate. So, when referring to the gut microbiome, that effectively means a small ecosystem, in this case of bacteria, fungi and viruses, that live inside us, nestled in our guts, aka our intestines. Just to shed light on the sheer magnitude of this amazing ecosystem, the small intestine is around 9-12 feet long (or >2.5m), and the large intestine is around 5 feet (>1.5m). With trillions (not millions or billions, trillions) of bacteria that inhabit this snaking tube, bacteria alone outnumbering our own cells 1.3 to 1, it’s a vast world that bathes us and shapes us, even though it’s a world that we can’t see, hear, or even feel! In fact, the large intestine alone has the most diverse number of bacterial species of any human microbial (meaning tiny life form, and its use here refers to bacteria) community studied so far, with anything between 300 and 1000 species.

Now, it is important to differentiate between a microbiome and the gut microbiome specifically. Gut aside, we also have a skin microbiome, oral microbiome, nose microbiome and more. The bacteria that inhabit the vagina, for example, is somewhat different to the inhabitants of our guts, or skin, lungs, or hair.

How did we get this gut microbiome?

During birth, we are covered in our mother’s vaginal and faecal microbes, some of which get inside us, before the consumption of solid food kick some of these bacteria out to replace them. Our gut microbiomes change and fluctuate quite a bit until late childhood, before stabilising and remain relatively stable through adulthood, but ratios of bacteria can shift in accordance with certain foods we eat, diseases we may be afflicted with, or environmental toxins that we are exposed to. As previously mentioned, although we are made of plenty of microbiomes, the gut’s is by far the largest and most significant regarding its contribution to our short and long-term health.

What’s the big deal?

For a first, our microbiome produces beneficial compounds for our health. Have you heard of these things called SCFAs, or short chain fatty acids? These are produced during the fermentation of soluble fibres by our gut bacteria, fibres that are in foods like grains, avocados, and sweet potatoes. SCFAs can trigger downstream effects that include influencing how the body reacts to bad guys like foreign pathogens and bacteria, and reducing inflammation, the root of most physical and mental health issues.

SCFAs are just one of many things our bacteria secrete that influence our health. They also produce neurotransmitters (chemicals that transmit signals in the brain) such as serotonin, GABA and glutamate, that need to be preserved in a delicate balance, to support a positive mood and healthy outlook on life. Other reasons to be grateful for our gut include but are not limited to: the production of vitamins such as vitamins B and K, amino acids, and amino acid metabolites. Metabolites are the products of metabolism, which is the process of maintaining life itself, such as repairing damage and breaking down food into smaller bits to be absorbed. All these processes contribute to the healthy activity of many organs like the heart and liver, and can also contribute to histone modification (which is how tightly DNA is wrapped and how DNA is expressed). SCFAs can even serve as energy sources for mitochondria, which, if you remember anything from high school biology, serve as powerhouses of the cell and generate energy using oxygen for our usage.

Moreover, the beauty of the gut microbiome lies in its ability to change. For example, if your microbiome is damaged, due to taking a course of antibiotics, or food poisoning (both of which wipe out a lot of beneficial bacteria in your gut), not all is lost. By implementing a balanced and healthy lifestyle, alongside a gut-nourishing diet and some probiotics (which are bacteria trapped in a capsule and are only released when they get to your gut, after its journey through the stomach), your gut composition will return to normal, sometimes in less than a month. Unlike the narrow flexibility of the other microbiomes that inhabit us, the gut is forgiving and able to be manipulated to our benefit.

The gut as a medium for personalised medicine and revolutionary therapeutic approaches

Given the malleability of the gut and its important role in our health, a lot of research has investigated potential ways to optimise the gut microbiome to complement therapies and medications for a wide variety of diseases. This, of course, includes personalised approaches. Today’s push for personalised medicine is partially driven by reduced costs to sequence people’s genomes (our DNA makeup), which have allowed us to figure out exactly what issues lie therein, before applying a precise and tailored medicine regime for optimal recovery. Now, with the ability to sequence the DNA of one’s gut microbiome, it is possible to identify which are the dominant species living in one’s gut, and thus possible to form (at the very least) associations between bacteria subtypes and certain maladies, be it irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, and even mood disorders such as anxiety or depression.

What now?

There is a new and exciting market for microbiome products born of newer research linking gut microbiome species to different ailments, which is what we at Mibio are hyped about. We are passionate about bringing new solutions to old and stubborn health issues. It is truly an exciting space to be in now, destined only for better and more efficient solutions and therapies!

To conclude, our guts host an important ecosystem that influence our health in many important ways, and now is the time to capitalise on growing research surrounding the gut microbiome and we can tailor and personalise medications and supplements to optimise our guts.